Competency in counselling therapy is grounded in the emotional intelligence of the practitioner, in a complex and flexible working model of human functioning and in knowledge and clinical skills acquired from a wide variety of learning sources.

Our profession became more formally established in the latter half of the 20th century out of the confluence of psychiatry, pastoral work, and social work. As it evolved, the profession found its home primarily within academic graduate school departments of psychology or education and schools of social work or divinity.

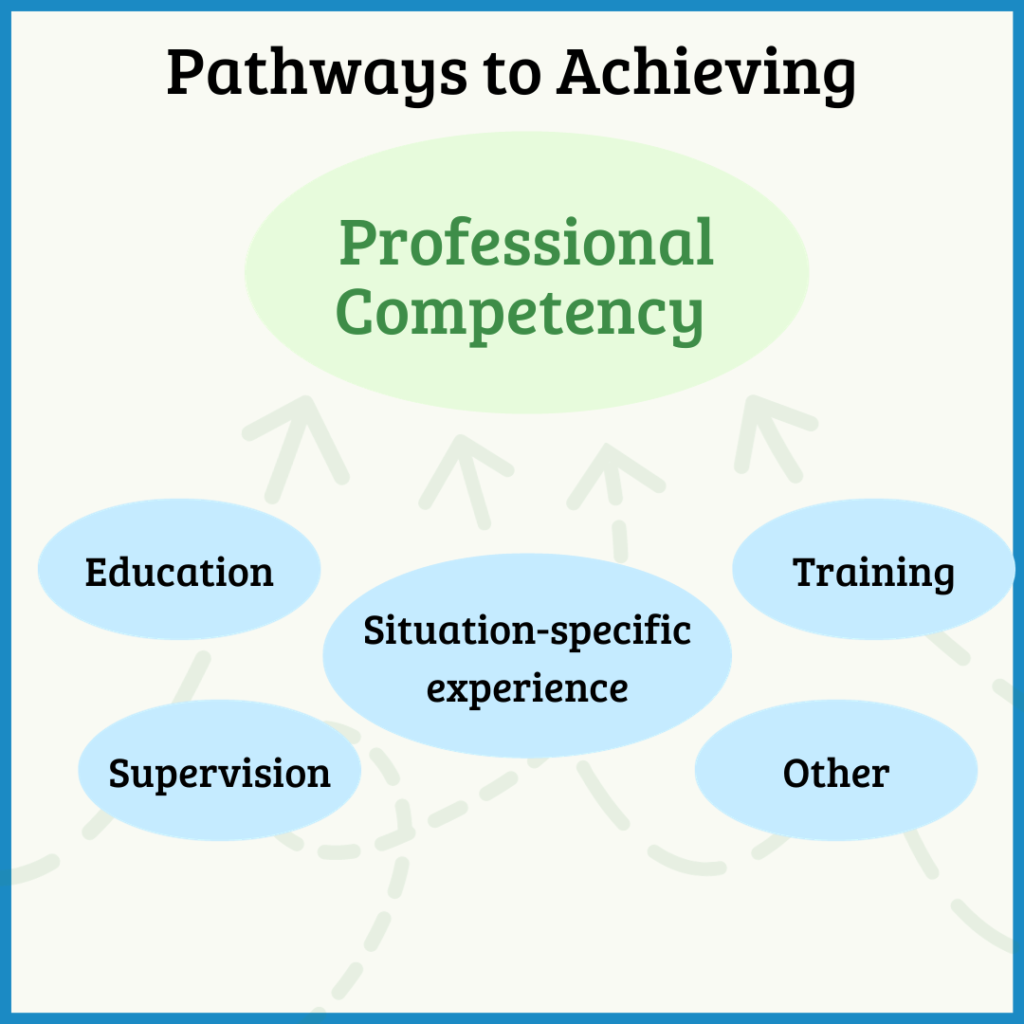

The role of academic credentials is thus largely a consequence of our history, but with the rise of competency-based models within our profession and many others, it is clear that professional competency can also be achieved through many pathways.

Education

Formal training programs offered through universities, colleges or private institutions provide opportunities for students to learn about various (current and historical) theoretical descriptions or models of human functioning, such as the views of psychodynamic, existential, and cognitive / behavioural theorists, among many others.

Exposure to these ideas in school is usually combined with recognizing the importance of development within one’s career and with the notion that these ideas will become refined, extended, rejected or sometimes forgotten on the basis of how helpful they show themselves to be in the practitioner’s growing experience.

Training

As with most professions, counselling therapy includes specific clinical skills which are essential in the delivery of service.

Most counselling therapists start their careers as apprentices, learning basic skills through imitation and practice, perhaps in a specific skills-oriented course as part of a formal program or alternatively, through intensive observation of a mentor’s work. The skills in an apprentice / mentor situation usually focus on building and maintaining an intentional relationship for therapeutic purposes; for instance, specific interventions such as motivational interviewing in talk-therapy training.

Later in one’s career, new sets of skills are often acquired through supplementary and stand-alone training experiences. Examples of this would be training sequences which lead to certifications of specific practice-centered skill sets such as CBT or EMDR.

Supervision

Although each of us has the inside track regarding access to our own immediate experience, our ability to step outside that experience and accurately evaluate our own work in a counselling session is often biased. Our self-assessment abilities range between being “our own worst critic” and “I’m awesome” (well, maybe not that bad). So the counselling therapy profession has developed a highly specialized feedback practice called ‘clinical supervision’.

In clinical supervision, a contractual agreement is made between a counselling therapist and a trained supervisor. The therapist agrees to demonstrate their counselling work to the supervisor, who in turn agrees to provide directive and constructive observations regarding the content and process of counselling.

Early in a practitioner’s career, the supervisor actively monitors and ensures client safety while helping novice therapists navigate the challenges of their work. As the therapist’s skill levels improve, the supervisor’s feedback usually highlights competencies that need further attention and provides direction and support for the struggles that most of us experience.

For instance:

- How did I miss that?

- I couldn’t understand what my client wanted.

- I know what they need to do, but they just won’t listen to my advice!

Situation-Specific Experience

Some competencies are formed through experience arising from situation-specific requirements. For example, counselling therapists are expected to be informed about cultural safety and humility, but it is through direct experience that these competencies are acquired and then applied when a counselling therapist works with people within specific cultures and other self-defined identities.

Similarly, working within the specialization of relationships (couples, families and communities) also requires focused training and experience beyond what is needed to work with individuals.

Work settings often provide unique challenges and opportunities for growth. For example, custodial settings: working in correctional services, long term care, foster care can create an understanding of the role of social control issues not usually present in other environments.

Another example would be working with clients who are recent immigrants or persons who are unhomed or in shelters. This work can highlight themes around advocacy and social justice.

Other Sources

Developments within the technical sphere of the counselling field can produce challenges and provide opportunities for achieving new competencies. For example, over the last decade, tele-mediated service delivery requires a counselling therapist to become familiar with new requirements regarding jurisdictional necessities and security arrangements in addition to those arising in face-to-face work.

Summary

If our goal is to solidify a competent profession that is able to offer all British Columbians an opportunity to access counselling therapy services that are right for them, then would it not make sense that we use ‘competency’ as the overarching measure while building the profession?

How one achieves that competency is the beauty of this model. Competency in this field can be achieved through multiple pathways and then assessed and mapped appropriately.

All British Columbians deserve the right to be supported by a competent practitioner who is accountable to their clients and whose regulated status increases public protection to all.